Our Planet: Behind the scenes with a one tonne walrus

Our Planet, our new documentary series narrated by David Attenborough, shows walruses as you've never seen them before - and the threats they face.

On land, they’re hulking, belching, flatulent one tonne beasts boasting a substantial layer of blubber. They're protected by skin around 4cm thick, which is amongst the thickest skin in the world – human skin is only around 1.3mm thick. But most impressive are their long tusks and the stiff bristles around their mouths. They certainly make a statement.

They can live to around 40 years old, and it shows. Most of them carry a vast map of scars on their skin – wounds inflicted by fellow walruses when they gather in tightly packed haul-outs. As they jostle for space, they'll let their neighbours feel their displeasure with a sharp jab from a tusk. Walruses also use their incredible tusks for fighting, to form breathing holes and to haul their huge bodies onto the sea ice.

Underwater, they’re almost majestic. They make many strange underwater sounds – one of them is like a deep-pitched church bell. They’re rarely found in the deep, instead preferring to feed at the bottom of shallow waters around coastlines, mostly eating molluscs.

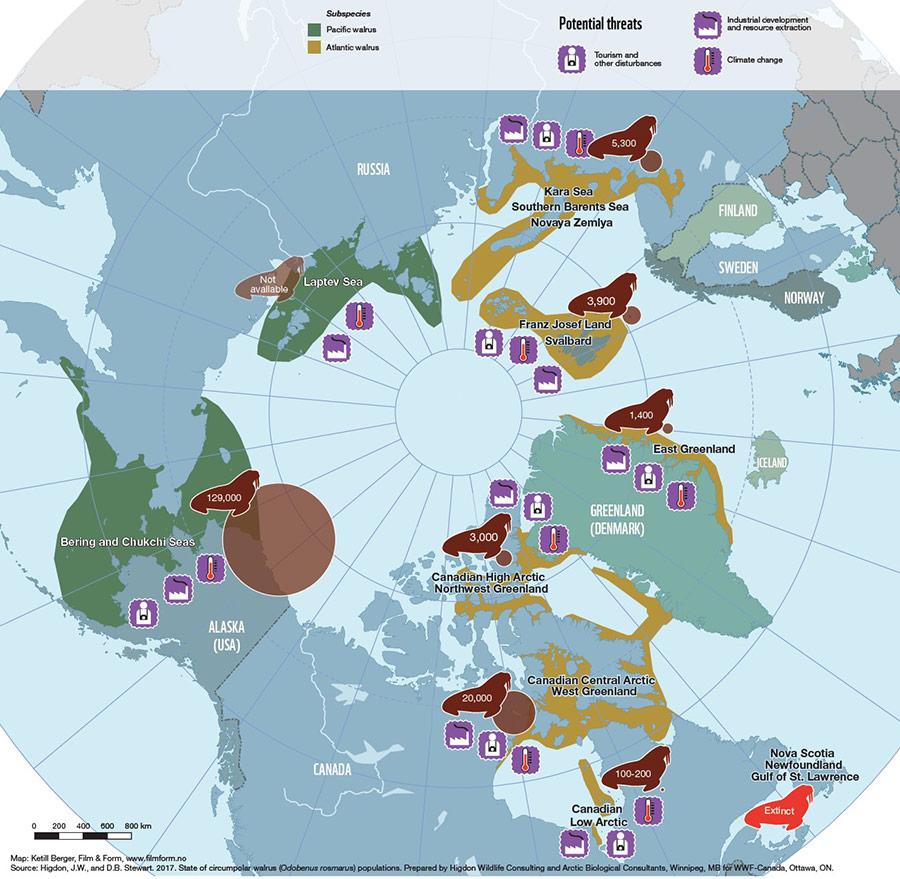

There are two subspecies of walrus – the Atlantic and Pacific – which both occupy different areas of the Arctic. But for both walruses, their world is changing fast.

Pacific walruses, like the ones in the Our Planet series, spend spring and summer feeding over the huge, shallow continental shelf in the Chukchi Sea. They use the sea ice as a platform for resting, and a place to leave young calves while they're diving for food.

In the past decade, a warming Arctic has meant summer sea ice has retreated hundreds of kilometres further north, forcing abnormally large numbers of Pacific walruses ashore along the coasts of Russia and Alaska - up to 100,000 at one site alone along the Chukotka coast in 2017.

But climate change isn’t just melting the walruses’ habitat - it’s introducing new threats.

New predators

Killer whales aren’t designed for ice – they have a large dorsal fin which could strike the sea ice, causing them pain (most Arctic whales have no dorsal fin). But melting sea ice means these predators have a whole new feeding ground to hunt in. And they hunt walrus.

On land, polar bears are also attracted to large haulouts - and the smell of carcasses. They not only disturb walruses but can endanger people in nearby communities.

Human disturbance

Unlike Pacific walruses, Atlantic walruses prefer to rest ashore, as most feeding grounds in the Atlantic are closer to land. This means they’re highly susceptible to disturbance and noise - from people, low-level aircraft and passing ships. This human-made noise is only set to worsen as diminishing sea ice makes the Arctic more accessible.

Industrial impacts

New opportunities for shipping routes, commercial fishing and infrastructure such as housing and harbours are opening up across the Arctic. These activities cause a huge amount of noise and break up existing sea ice, fishing can result in the accidental capture of walrus in nets, and bottom trawlers can destroy feeding grounds.

Oil and gas developers are also looking northwards, meaning walruses could face the risk of toxic oil spills - virtually impossible to clean up on ice.

What are we doing?

- We’re supporting research into walrus populations and feeding areas. Our findings enable us to make recommendations to better safeguard them.

- We’re working with communities to keep people safe, by removing walrus carcasses and scaring any polar bears away.

- We’re also speaking to tourist operators and shipping companies to reduce the risks to walruses, as well as researching walrus behaviour at haulouts and the effects shipping has on them.

- In Canada, we’ve produced a guide for mariners on the Hudson Strait to help them identify and report on walruses and their habitat, and teach them what to do during any encounters.

From the field

Tom Arnbom, our walrus expert, got up close and personal with walruses from the Laptev Sea.

Along the Russian Arctic coast is the Laptev Sea, where the Atlantic and Pacific walrus populations meet. Our mission was to find out if the walruses of the Laptev Sea were genetically unique from Pacific and Atlantic walruses, and therefore needed special protection.

The team and I crawled along the ground, trying to get as close to the walruses as possible without disturbing them. We managed to gather over 30 DNA samples using harmless “biopsy darts” which, when shot at a walrus, gathered a small skin sample.

The results proved that walruses from the Laptev Sea are similar to Pacific walruses, but they have some unique characteristics which warrant them being managed differently. This analysis was vital to protecting this population.

During our field trip, I noticed every walrus haul-out had a polar bear nearby. One walrus calf is enough to sustain a polar bear for a month. As sea ice declines, this is the future for some polar bear populations; scavenging on walrus carcasses or trying to hunt calves.

I’ve been working in the Arctic since the 1970s, and it’s a very different place now.

What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic

Climate change remains by far the greatest threat to walruses. If we don’t start to see climate change as an emergency and act now, sea ice will continue to decline and the risk to walruses will grow. And that’s the least of our problems.

12 ways to fight for your world

12 ways to fight for your world

Become a detective and spot walrus from space

Become a detective and spot walrus from space

Learn about the effects of climate change

Learn about the effects of climate change

Top 10 facts about polar bears

Top 10 facts about polar bears