Looking below the canopy

Previously, there was no global measure of changes to forest wildlife populations, despite the fact that more than half the species that live on land are found in forests.

Instead, progress was measured by the amount of tree cover or forest area. Using a newly created index – the Forest Specialist Index – we were able to look ‘below the canopy’ and found that forest populations of vertebrates (which include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians etc.) declined by 53% since 1970. Declines were greatest in tropical forests, such as the Amazon rainforest.

After studying 268 species, we also found that tree cover doesn't always reflect changes in populations of forest animals. Because they face multiple threats, continuing to use forest area as a measure on its own risks hiding the true condition of our forests.

A different perspective

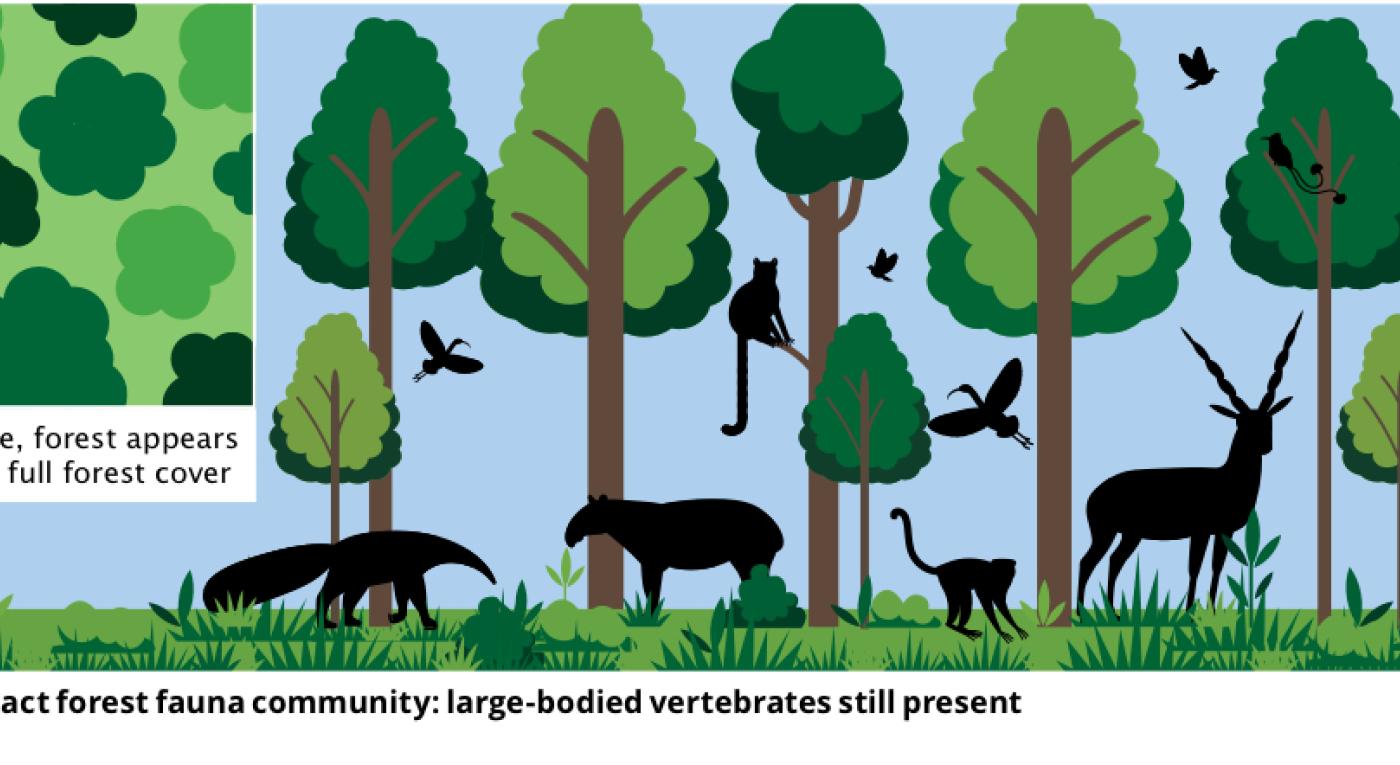

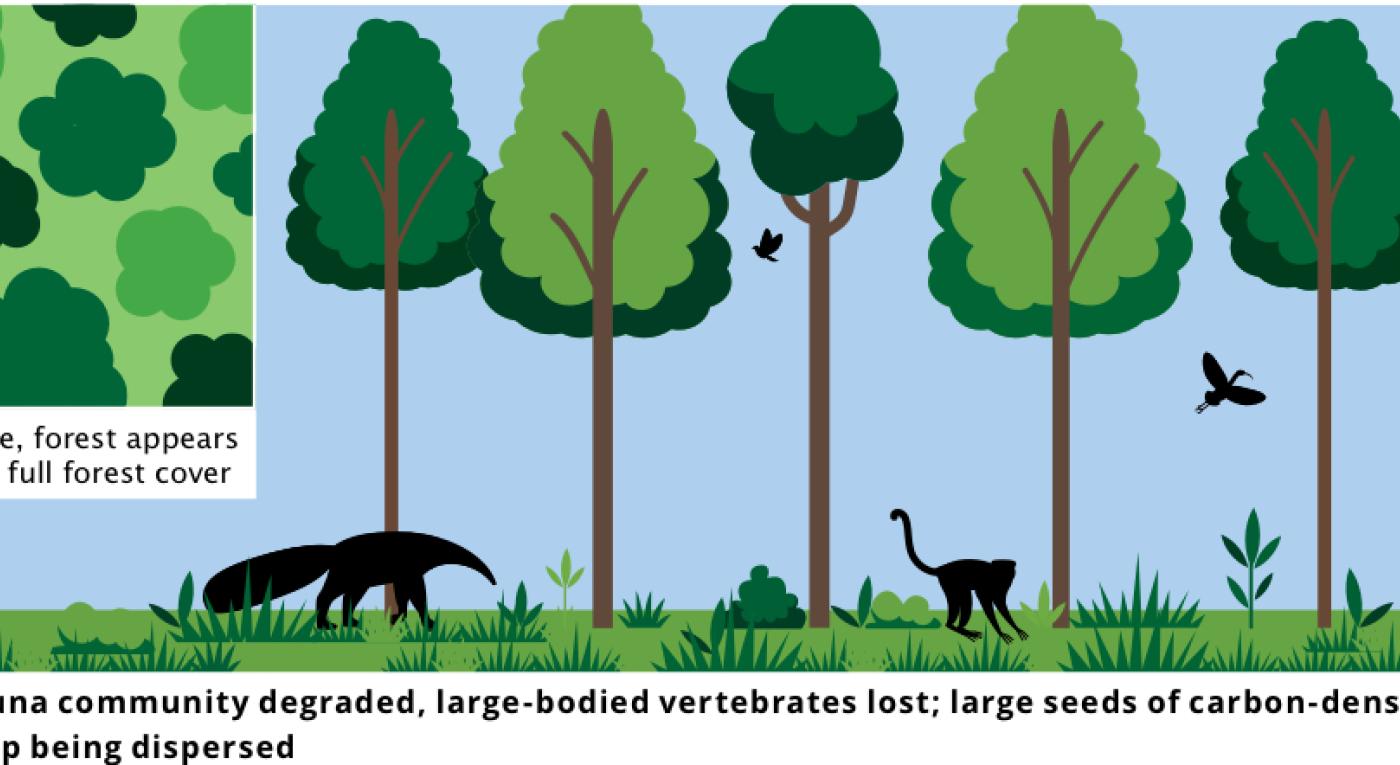

Drag the slider on the image below to see how looking below the canopy makes such a difference when measuring biodiversity of forests.

The link between wildlife, forests and the climate crisis

The link between wildlife, forests and the climate crisis

A decrease of 53% of wildlife populations in our forests over the last 44 years should be a major concern. The plants and trees in forests provide habitat and food for many species, and in return wildlife plays a key role in keeping forests healthy and helping them regenerate – the two rely on each other for survival.

For example, large fruit eating mammals such as primates (including monkeys and apes) are important for seed dispersal of carbon-dense trees. These trees store large amounts of carbon as they grow, taking it out of the atmosphere. Therefore, if we lose the large mammals in our forests over time the carbon dense trees do not regenerate and less carbon dense trees dominate, weakening our forests as an essential ally in avoiding dangerous climate change.

53%

decline in monitored populations of forest species

50%

of the worlds biodiversity lives in forests

60%

of threats were due to deforestation and degradation of forests

20%

estimate of Amazon Rainforest that has already been cleared

What is causing this decline in wildlife?

What is causing this decline in wildlife?

A major cause of loss of biodiversity is deforestation and degradation of forests – accounting for 60% of the listed threats to forest species in our database. Invasive species, climate change, disease and exploitation are also causing wildlife populations to decline. And 60% of populations we have analysed faced more than one of these threats. In order to reverse the decline, we need to address all these problems. In other words, tackling causes of deforestation is essential but not enough to protect and restore forest wildlife populations.

Helping wildlife recover

Helping wildlife recover

Despite the bad news, there have been some positive signs for some wildlife populations beginning to recover.

Mountain gorillas, for example, are faced with a number of threats. These include habitat loss and degradation as a result of agricultural expansion, competition for limited natural resources, diseases, and injury caused by snares left to catch other animals for bushmeat.

The good news is mountain gorillas are starting to show signs of recovery, both in the Virunga Massif and in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. While there’s a long way to go, this is something to genuinely celebrate.

We’re proud to have played our part in this success, which is down to sustained effort from government, civil society and the private sector, working together to tackle the multitude of threats. Actions have included enhancing law enforcement, improving tourism practices and working with local communities to ensure that they benefit from mountain gorilla conservation.

Forests

Forests

Eight tips to eat more sustainably

Eight tips to eat more sustainably

Join the fight for your world

Join the fight for your world