ECFT Blog Series | Issue #1 | June 2024

Introduction: environmental crime is bigger (and worse) than we think

The landscape is changing, and fast. This is true for natural landscapes – that is, the complex mosaic of ecosystems, species, and anthropic activities – and for regulatory landscapes. Under the growing pressure of human societies nature transforms, and laws and regulations follow.

However, while ‘Environmental Law’, as an umbrella term, is expanding at an unprecedented pace worldwide, the urgency of the climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution crisis is calling for governments, lawmakers, regulators, and other stakeholders to act both more efficiently and effectively. A recently published report by UNEP (2023, p. xi), summarises this issue well: “Although many countries worldwide have implemented various environmental laws, their effectiveness in practice remains a challenge for addressing the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.”

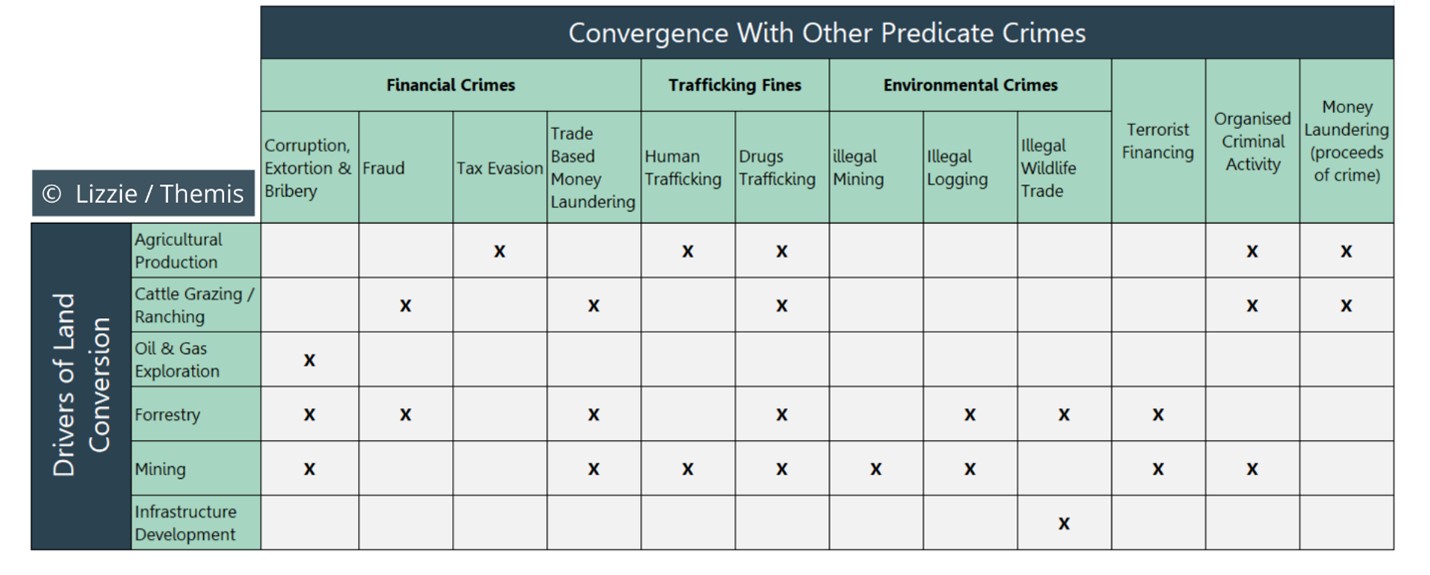

With new environmental laws, regulations, codes and guidelines rapidly piling up on the desks of legal and compliance departments worldwide, it is surprising how environmental crime – which is often happening outdoors, in plain sight – is rarely seen as a serious offence or correspondingly considered as a specific area of risk and due diligence. Notwithstanding the range of environmental criminal offences across the world, environmental crime per se is already a universal and ever-expanding area of law and regulation. The impact of environmental crime cannot be understated. According to the 2018 Atlas of Illicit Flows, environmental crime is more lucrative than human trafficking and – with an estimated value between USD 110 and 280 billion every year – is the third largest criminal sector worldwide. Yet, as with many large-scale crimes, environmental crimes rarely occur independently of other misconduct. Environmental crimes are often part of a wider web of criminal conduct, and overlap with an array of financial crimes and human rights violations that are well recognised and often prosecuted – as shown in the table below from a new joint report by WWF and Themis.

Figure 1 - Convergence of land conversion drivers with other predicate crimes

Scanning the horizon: new environmental laws and the implications for the financial sector

Now that we have settled the question on the importance and pervasiveness of environmental crime, we can go back to our initial point: the legal landscape is changing, and fast – So, what are the main implications for financial institutions? And what are the new key laws and regulations you need to know?

We mentioned already how environmental crime is increasingly associated with a number of predicate offences, with strong ties to financial crimes (bribery, money laundering, tax evasion, fraud, etc.) and human rights violations. There are two key points to make here as relevant to financial institutions. First, you may already have procedures, systems and controls in place designed to identify and mitigate exposure to these broader offences. If so, you should start considering now how these may be leveraged to monitor your environmental crime risk exposure (see further below). Secondly, the scope of any environmental crime investigation or enforcement action may reasonably cover such broader misconduct, which expose financial institutions to wider enforcement and reputational risks. Consider the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. The criminal case – where BP “pleaded guilty to felony manslaughter, environmental crimes and obstruction of Congress” – and related civil lawsuits led to “the largest environmental damage settlement in United States history – $20.8 billion”.

As the range of environmental offences grows, enforcement actions will not only focus on large-scale environmental disasters. Nowadays, financial institutions – in a growing number of jurisdictions – can be sanctioned ‘simply’ for brokering deforestation and land conversion within wider investment operations. As a consequence, there are also concrete regulatory and operational risks to be factored in, particularly for financial institutions that have direct and indirect exposure to deforestation, land conversion, and global trade in commodities such as palm oil, timber, soy, beef, gold, and fishing. Given the sheer breadth of these sectors, they likely touch on the vast majority of financial institutions – so you are not alone.

With new laws and regulations in the making, the environmental crime risk and sanctions profile is widening. Below we discuss some concrete examples, although this list is clearly non-exhaustive. For instance, the EU has recently passed a new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, which requires EU and non-EU companies with an annual turnover over 450 million Euros (or equivalent) to detect and address where their operations can have adverse impacts on human rights and the environment. Among other things, this new regulation introduces “injunctive orders and effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties (in particular fines)”, as well as “compensation for damages resulting from an intentional or negligent failure to carry out due diligence”.

With a similar rationale, but a focus on curbing deforestation induced by EU consumption across global commodity supply chains, Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 on deforestation-free products also establishes a framework to impose corrective actions and penalties. Listed in Article 25, potential penalties – among others – include fines of “at least 4 % of the operator’s or trader’s total annual Union-wide turnover in the financial year preceding the fining decision”, “temporary exclusion for a maximum period of 12 months from public procurement processes and from access to public funding”, and “temporary prohibition from placing or making available on the market or exporting relevant commodities and relevant products”. Despite some differences, the UK is also introducing a new Due Diligence Regulation on Forest-Risk commodities, and a number of countries worldwide are currently considering similar approaches. It goes without saying that any such enforcement action could have a huge financial, administrative and reputational impact on any financial institution.

One last thing – and it’s good news! The Environmental Crimes Financial Toolkit

Let us part ways on a bright, collaborative note. We understand that the number and scope of new environmental crimes and offences across the world, and the increased compliance burden with respect to due diligence requirements (notably regarding land conversion, deforestation, and human rights violations), can pose a challenge to financial institutions. However, as the level of complexity grows, new instruments are being developed to help the banking and financial sectors manage their exposure to these risks. Specifically, a new Environmental Crimes Financial Toolkit is currently being developed by WWF-UK and Themis, supported by the Climate Solution Partnership. With the first version of the toolkit due to be released by the end of 2024, the intention is that financial institutions can add this new tool to their compliance arsenal to help identify and mitigate certain environmental crime risks.

This Toolkit, for the first time, addresses the convergence between financial crimes, predicate offences, and environmental crimes related to deforestation and land conversion. By highlighting red flags and risks connected with different types of environmental and financial crimes, the Toolkit helps financial institutions leverage and strengthen their screening and diligence procedures whether onboarding new customers/counterparties, reviewing existing ones, or assessing your sectoral risk exposure more generally. While new regulatory requirements come with new challenges, the solution space is also becoming vibrant and rich, providing opportunities – for those willing to seize them – to adapt, react and possibly carve out a competitive advantage out of this regulatory transformation. We at WWF want to work with you to achieve that, and proactively identify and reduce your risk exposure to environmental crimes.

Have a question about this article?

Get in touch: ecft@wwf.org.uk